How an early Chinese-American fishing village fuelled shark fin trade before being burned to ground – Technologist

On May 26, 1906, a fire swept through Point Alones, California, devastating one of the largest Chinese fishing communities in America, with newspaper reports suggesting the fire was started by nefarious individuals, evidenced by the water hoses being cut and direct anecdotes of looting.

The legendary American author John Steinbeck visited the village in his younger years and, decades after the fire, said about Point Alones: “I remember the night the whole thing burned to the ground. We felt that a way of life was gone forever.”

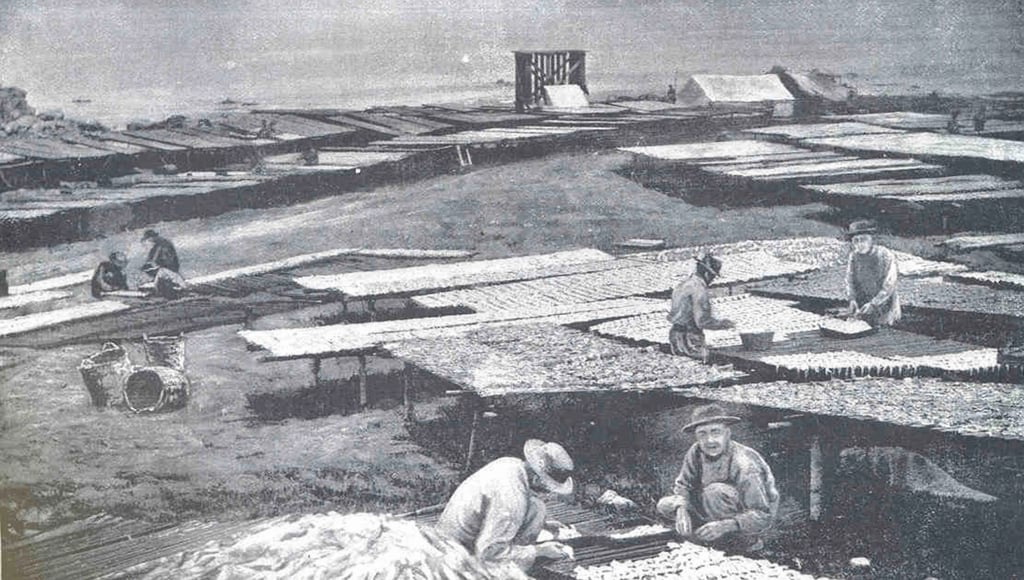

Before it burned down, Point Alones was a crucial fixture in the global shark trade. Sharks caught in Monterey Bay were often processed, and dried shark fins were sent to China as premium products, according to a study published in the peer-reviewed journal Human Ecology in late June.

“While much of the fish harvested by these villages was being exported to China, some was being shipped to other Chinese settlements in the American West, including railroad work camps,” said Thomas Royal, a study author who works at both Simon Fraser University in Canada and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Norway.

“For instance, one account from 1882 notes Chinese fishers in California were shipping dried and salted grey smooth-hound to Chinese railroad labourers.”

Royal told the Post that the village was initially started by migrants from Guangdong province in southern China in the middle of the 19th century. He said oral histories suggest the initial settlers may have landed at the location due to a shipwreck. The new arrivals brought with them “a deep knowledge of fishing”.

The study aimed to paint an in-depth picture of how the Point Alones community harvested sharks, including details about the species they targeted and how the animal was processed for sale.

The researchers analysed the DNA from 54 shark vertebrae and learned that the fishermen were likely harvesting sharks from the local waters around Monterey Bay, a widely-known diverse ecosystem off the coast of California.

The most common sharks the fishermen caught were tope sharks, which were widely harvested in the US in the first half of the 20th century. Later, white-owned commercial fishing companies in the 1930s and 1940s heavily exploited the species and tope sharks became one of the country’s most important sources of Vitamin A during World War II. The sharks have since been added to the global critically endangered list.

Royal said that while tope sharks were expected to be discovered in the vertebrae analysis, their dominance was surprising. The researchers only found three species of sharks in the research (the other two being leopard sharks and brown smooth-hounds), and the tope sharks outnumbered the other animals at a rate of five-to-one.

“This suggests that the Chinese fisheries based at Point Alones were being fairly selective when it came to sharks, preferentially harvesting tope sharks,” said Royal.

Royal hypothesised that because the sharks typically lived closer to the shore, they were likely being fished when workers went out at night to hunt for squid, which was also economically important to the village.

Much like today, these sharks were being harvested in California to feed the craving for shark fins and tails in China.

American fishermen would tap into the personal network of businesses, friends, and family from the mainland, facilitating the movement of goods, money, people, and knowledge between China and the US.

Hong Kong businesses called Jinshanzhuang or “Gold Mountain firms” specialised in shipping goods between the two countries, and the Monterey Bay area (which included Point Alones) became a hotspot for international trade.

One estimate said 100 tonnes of dried fish were being shipped from California to China yearly. Dried shark fins were a particularly valuable commodity in this trade.

The researchers believe the Point Alones fishermen were not “finning” the sharks —cutting off the fins and tails of the sharks while they were still alive and dumping them back in the water — which is a fairly common practice today.

Point Alones fishermen typically brought the whole shark back to the village for processing. Its meat was sold throughout America, and the liver and carcasses were turned into oil and fish meal for markets.

The fishing village at Point Alones appeared to have been moderately successful financially, and selling a pair of shark fins was enough to cover a day’s wage.

“The trade in shark fins did provide the inhabitants of Point Alones with a degree of wealth, but it wasn’t making them rich,” said Royal.

A major challenge for Point Alones at the time was institutionalised racism from white Americans. Private and public individuals expressed “concerns” about the Chinese fishermen’s impact on the local animal population, but these fears were driven by racial resentment.

As a result, local governments passed laws to make fishing a headache for the Chinese population, and white fishermen would often physically and verbally intimidate the workers.

Royal said some restrictions included “a ban on Chinese participation in commercial fishing, a prohibition on shrimp fishing (which was popular among Chinese fishers) during months when shrimp were abundant, and restrictions on the use of gear preferred by Chinese fishers.”

One goal of the study is to help modern conservation efforts. Royal said that understanding the history of fisheries can help scientists identify when humans began to impact local populations and adjust conservation targets accordingly.